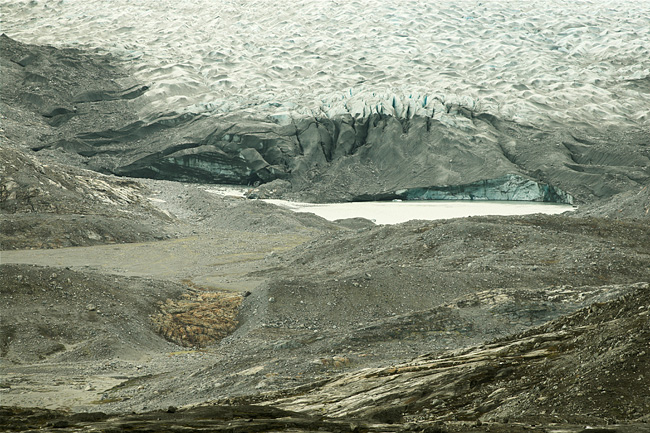

LakeThe meltwater from the Kangiata Nunaata Sermia forms a big lake, called Uukkaasup Tasia or Isvand. Since the glacier is moving downward to the sea, here from right to the left, it doesn't calve much ice into the lake. It's just the water from inside the glacier that accumulates in this lower spot of land. However, there must be a way for the water to also escape underneath the glacier, a drain that must have opened a couple of years ago as a result of a warmer climate. The water level of Isvand has fallen quite a bit as can be judged from marks on the lake shore, and not without consequences. |

End of IceSurely from time to time a chunk breaks off, but this doesn't happen too often as the ice is not really being pushed forward towards the water. The ice is just a passer-by who moves on down into the fjord. Ice doesn't behave just like a viscous liquid. While it pushes ahead it follows more complex rules, it breaks, tumbles, melts, flows as water, freezes over again, shows plastic flow at great pressure, slides along rock, slides on water films, falls down steep slopes, is shattered to pieces, sinters to a solid block. A part of it evaporates. And a lucky piece ends up swimming in the fjord.

|